Let’s look at an “easy” starting example: write

We know how that goes: multiply both sides by to get

and then since this must be true for ALL

, substitute

to get

and then substitute

to get

. Easy-peasy.

BUT…why CAN you do such a substitution since the original domain excludes ?? (and no, I don’t want to hear about residues and “poles of order 1”; this is calculus 2. )

Lets start with with the restricted domain, say

Now multiply both sides by and note that, with the restricted domain

we have:

But both sides are equal on the domain

and the limit on the left hand side is

So the right hand side has a limit which exists and is equal to

. So the result follows..and this works for the calculation for B as well.

Yes, no engineer will care about this. But THIS is the reason we can substitute the non-domain points.

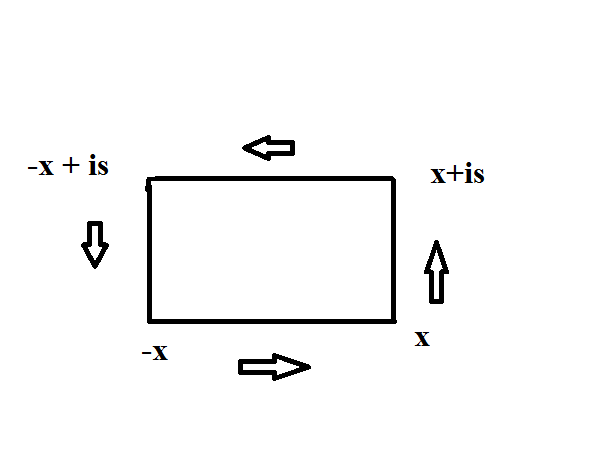

As an aside: if you are trying to solve something like one can do the denominator clearing, and, as appropriate substitute

and compare real and imaginary parts ..and yes, now you can use poles and residues.